The Cyber Attack Perception Problem in 2023

Looking for the most recent version?

Click here!

It’s here! The 2023 update to our research on the perception of cybersecurity incident and data breach causes that’s helped organizations re-evaluate how they are at risk of a cybersecurity incident or data breach instead of what feels right. So what’s new this year, what was our methodology, and what was surprising? Keep reading below! Or download now!

Let us know what you think on social media!

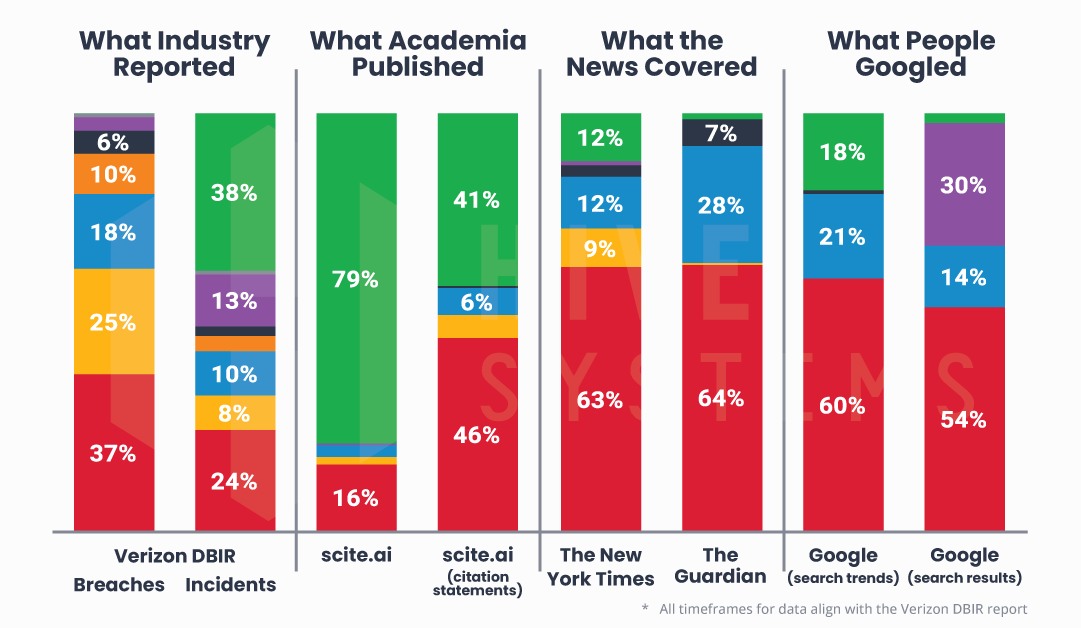

For the past few years (2020, 2022), we’ve shared our research on the data breach perception problem - pointing to the fact that how data breaches occur appears to vary widely between industry sources and how people think they may occur. With another year’s worth of data and looking for opportunities to expand our work, we’ve decided to expand this year’s data to not only look at cybersecurity data breaches, but incidents as well - so looking at all successful cybersecurity attacks! We’ll walk you through our methodology, our updates, and some surprising findings!

Verizon’s 2023 Data Breach Investigations Report (DBIR)[1], an industry publication that analyzes cybersecurity incident and data breach event data from around the world, found that over 99% of all events fall into one of eight major categories:

Patterns over time in cybersecurity incidents. Source: Verizon DBIR [1]

Patterns over time in cybersecurity data breaches. Source: Verizon DBIR [1]

In last year’s DBIR report[2], Social Engineering and Basic Web Application Attacks accounted for over 50% of all cybersecurity data breach events, with Denial of Service being the number one cybersecurity incident covering almost 50% of all events. In the 2022 DBIR report, System Intrusion took the lead, accounting for 40% of all data breach events, with Denial of Service remaining in the top spot for cybersecurity incidents with System Intrusion moving into a close second spot. Now, in the 2023 DBIR report, System Intrusion has plateaued for cybersecurity data breaches but remains in the lead with both Denial of Service and System Intrusion holding the top spots for cybersecurity incidents.

“What do these categories mean?”

Verizon in the DBIR defines cybersecurity incidents as events that impacted the confidentiality, integrity, and/or availability of data. Cybersecurity data breaches are defined as cybersecurity incidents that resulted in the confirmed compromise of data confidentiality i.e. the unauthorized viewing and/or copying of data.

For example, DDoS attacks and unauthorized encryption (e.g. ransomware) were not a “data breach" unless attackers were able to view or copy/ transmit data out of the environment.

The DBIR categories (classification patterns) were based on rough statistical clustering of data, not how the cybersecurity industry tends to group them so we’ve provided a bit of clarification below. Here are some examples of the types of cybersecurity incidents and data breaches that fall within each group:

System Intrusion: hacking, ransomware, malware, exploiting workstation software (e.g. Plex for LastPass breach) stolen credentials, RAM scrapers. Usually relatively many steps are required to execute these.

Basic Web Application Attacks: SQL Injection, exploiting vulnerabilities, using stolen credentials. Password stuffing, cracking, guessing, spraying. Usually relatively few steps are required to execute these so they are called basic.

Social Engineering: phishing emails, texts, phone calls.

Miscellaneous Errors: misconfigured server, email sent to the wrong person etc. directly resulting in compromise of confidentiality, integrity and/or availability.

Privilege Misuse: disgruntled employee e.g. posts sensitive data publicly

Lost and Stolen Assets: laptop or phone left in cafe or pickpocketed

Denial of Service: DDoS and DoS based attacks

Everything Else: things like ATM card skimmers

What influences our perception of successful cybersecurity attack causes? Do those perceptions reflect reality? If the news media and the internet are leading us astray, maybe we can pinpoint what those influences are and systematically reduce our bias on those topics.

One way to address the question of what we perceive as cybersecurity incident and data breach causes was inspired by Hannah Ritchie and Max Roser’s 2018 article[3] comparing causes of death data to what The New York Times, The Guardian, and Google Trends covered as causes of death. We adapted their approach to investigate the perceptions of cybersecurity incident and data breach causes. We looked at five sources of data - The New York Times, The Guardian, Google Trends, Google Search, and scite.ai - to compare how frequently their cybersecurity breach and incident coverage fell into each one of the DBIR’s classification patterns.

📆 Note that the DBIR is based on data characterizing events that took place between November 1, 2021, and October 31, 2022 so all of our time frames for the other sources align to this.

Analysis

“What are the perceptions of what caused cybersecurity incidents and data breached?”

We were interested in comparing what the DBIR, Google, news outlets, and academia reported as the causes of cybersecurity data breaches like we did last year but for the new 2022 data AND the inclusion of cybersecurity incidents. To that end, we refreshed our keywords and search terms related to cybersecurity incidents and data breaches for each of the eight DBIR categories. We searched for those terms across Google Trends, Google Search, The New York Times, The Guardian, and Scite.ai.

In the past we leveraged each outlet’s search feature or Application Programming Interface (API) and then sampled the results to ensure the results were actually cybersecurity related. This time around we used Google’s search feature to search the non-Google sources. We found Google did a much better job filtering out spurious results and catching big keywords that were semantically unrelated to the themes but socially/topically very much related e.g. log4j. Using Google’s domain search feature we inspected the search results for semantic context (e.g. phish email, not Phish the band), and tallied the number of hits in each category by outlet. Since we were interested in relative shares, we normalized the remaining counts by dividing them by the total for the year. We also added in the DBIR’s cybersecurity incident counts instead of only including the DBIR’s cybersecurity data breach counts. Here’s what we found:

People create and engage with cybersecurity content for many reasons. Since our approach here was exploratory, we made the assumption that people tend to turn their attention and subsequently dedicate their resources to cybersecurity content that they feel will solve their most pressing cybersecurity problems (likely based on what they feel is the biggest risk).

Here are some insights we can draw from our analysis:

“What caused cybersecurity incidents and data breaches?”

In this year’s report, the DBIR listed System Intrusion (that includes hackers and malware, including ransomware attacks, but not web application attacks) as the top cause of cybersecurity data breaches, followed by Basic Web Application Attacks, and then Social Engineering (the same order as last year’s report).

For cybersecurity incidents the DBIR listed Denial of Service as the top cause of cybersecurity data breaches, followed by System Intrusion, and then Social Engineering (the same order as last year’s report as well).

As in previous versions of our research, we used these as our baseline:

“What did academic research say about cybersecurity incidents and data breaches?”

Academic publications aligned most closely with DBIR in terms of coverage proportion across topics in the past but not so much this time around. Social Engineering was dwarfed by Denial of Service in the case of research papers, while System Intrusion was the focus of citation statements (which includes citing other research papers, including previous years’ papers), with Denial of Service in a close second.

“What did the news report as having caused cybersecurity incidents and data breaches?”

Like last year, The New York Times covered Denial of Service attacks more than the Guardian (12% vs 1%). The Guardian covered more Privilege Misuse while The New York Times covered more Basic Web Application Attacks. Both news sources heavily covered System Intrusion and Social Engineering events.

“Why did Denial of Service and Basic Web Application Attacks receive so little coverage from The Guardian in 2021 and 2022?”

Google’s thematic “translation” of search terms should be correcting for it to some extent but it is possible that we’re just not capturing the keywords used by the Guardian. We considered that maybe The Guardian realized their readership has no interest in these topics. To test that theory we compared Google Trends results between UK and US:

But it looks like folks in the UK are just as curious about Denial of Service and Basic Web Application Attacks. If you as a reader have any ideas or insights, let us know below!

“What did ‘the internet’ think caused cybersecurity incidents and data breaches?”

Googlers once again seemed largely preoccupied with System Intrusion events (ransomware, malware, hackers) with Social Engineering staying around 15-20% of relative searches.

“What content was available to us this time around if we did a Google search?”

In last year’s research, nearly half of the Google-able internet’s share of these topics was content mentioning System Intrusion, followed by Lost and Stolen Assets, particularly smartphones, and Social Engineering. For the third year in a row, these three categories shadowed all others. There were plenty of search results about cybersecurity concerns, but they did not align closely to the DBIR data which could be proportionally problematic.

“Did popular Google searches align with cybersecurity incidents and data breach causes or did they miss the mark?”

What we Googled was information about System Intrusion, Social Engineering, and Denial of Service. But in terms of actual search results, what we got was a lot of “How to locate your stolen iPhone” and other lost/stolen device content. Super useful for some, but not all.

Methodology

To perform the searches, we compiled a large list of keywords and search terms (like “phishing” or “social engineering”) for each of the eight DBIR cybersecurity incident and data breach categories. We collected the initial keywords and terms from the 2023 DBIR report, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Glossary of Key Information Security Terms [4], and from the cybersecurity professionals at Hive Systems. We entered the lists into Google Trends and added the resulting related queries suggested by Google to the respective lists. We repeated the process until the Google Trends related query results were no longer related to the respective DBIR categories. This was particularly helpful because it ensured we included terms like the names given to ransomware strains in our searches for “ransomware,” which are the terms people actually use in their search queries.

Counting Google Trends Results

We first entered the keywords and terms into Google Trends, but ended up getting more relevant results by using Google Trends’ Topics feature. We went with Topics because the feature includes synonyms as well as multiple languages. We also tested using all combinations of Google Trends Topics and Google Categories in order to find which combination of Google Trends settings yielded the most accurate results and the largest number of results. Trends Topics are useful because they include concepts based on your keywords e.g. if you use the topic “London” Google silently includes results for searches of "Capital of the UK" and the words for London in other languages. Trends Categories are also useful because they narrow down concepts to your subject of interest e.g. searching for the term “jaguar” yields results for the animal and car manufacturer of the same name unless you specify one or the other category. What yielded the most results and the fewest errors was using the category "Computers & Electronics" and the trends topics "Web application security,” “phishing,” “security hacker,” “insider threat,” and “denial-of-service attack."

Counting Google Search Results

We sampled Google search results for relevance by reviewing the last pages in each result set -- pages that Google finds least relevant. We counted results only on pages with results that were related to the topic being queried. We based relevance on the Google preview of the content.

Normalizing the Counts

Since we were interested in relative shares of cybersecurity incident and data breach causes by cause group, we normalized each data source's values by dividing the number of reports in each category by the sum of all reports for the time period.

Caveats and Limitations

Our results are based on a convenience sample and we cannot claim that our findings are representative or generalizable.

We did our best to put together an extensive list of cybersecurity incident and data breach cause synonyms, including colloquialisms, but don’t claim to have used an exhaustive list.

None of the data sources we used provide raw output (even with their APIs), so the algorithms and biases of the search engines and sources will have influenced these findings.

Google Trends allowed us to pool results from multiple languages, but other sources presumably did not. Google Trends results may be skewed toward results in languages that happen to talk more about one of the topics.

We evaluated Google Search results using the Google summary blurb, but it is possible the blurbs were misleading and that reviewing the whole article is necessary. We were unable to do so due to volume, but could use sampling in the future.

Cybersecurity professionals and people under cyber attack may be more discrete in their searches and opt for search engines like DuckDuckGo instead of Google.

The search engines and news sites we chose are obviously not the only options. We chose them for their convenience (how many search engines have something like Google Trends?) and because of their prominence, coverage, and familiarity to our readers.

If you find a good informative result or article for your search, do you keep Googling it? Any topics people found quickly, they presumably searched for less. This means that good writers are throwing off our stats!

What do you think? Tell us!

Join the discussion below or message us on social media and keep us honest!

If people seem interested in this sort of thing we’d like to add more stacks to the graphic like Wikipedia, Reddit, LinkedIn, Google patent search, security conferences, WayBack Machine, or other search engines.

References

[1] Widup, Suzanne & Pinto, Alex & Hylender, Dave & Bassett, Gabriel & Langlois, Philippe. (2023). 2023 Data Breach Investigations Report. Retrieved from: ‘https://verizon.com/dbir’.

[2] Widup, Suzanne & Pinto, Alex & Hylender, David & Bassett, Gabriel & Langlois, Philippe. (2022). 2022 Verizon Data Breach Investigations Report. Retrieved from: ‘https://www.verizon.com/business/resources/reports/2022/dbir/2022-data-breach-investigations-report-dbir.pdf’.

[3] Hannah Ritchie and Max Roser. (2018) "Causes of Death". Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://ourworldindata.org/causes-of-death'.

[4] National Institute of Standards and Technology (2019) Glossary of Key Information Security Terms. Retrieved from: ‘https://csrc.nist.gov/glossary’.